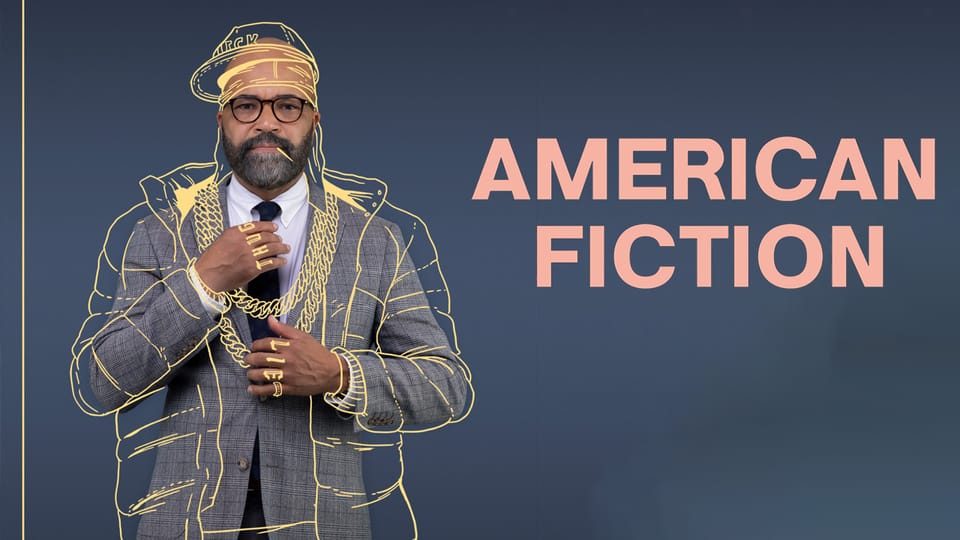

What Writers Can Learn From the First Page of American Fiction

American Fiction by Cord Jefferson has won loads of awards (including best adapted screenplay oscar!), so it’s probably no surprise to anyone that I enjoyed it. It is one of these movies that inspires me to write better stories.

It also gave me the idea of a new blog series examining the very best of what I read and watch, and to try and explain why these scripts, books and stories are so strong. What can writers take from exemplars? How can we adapt our writing in response to the sublime material that’s already out there?

Case study: American Fiction

You don’t need to read or watch much of this movie to understand what I’m going to say in this post. I’m only going to be talking about the first page. The first minute of this movie is incredibly well crafted. It is a fantastic example of an opening scene setting up not only the main character but also the theme of the film.

I’d highly recommend reading the first page – or taking the time to watch the movie – so that you can follow along with what I’m writing.

American Fiction: A Character Introduction Masterclass

Setting up characters well has always been a challenge for me. Too often I fall into cliché or exposition. It could be because it’s usually the first thing I write, and therefore I’m trying to get all the ideas down asQuicklyAsPossibleLikeThis.

So there’s a lot I can learn from American Fiction. The writer has a clear objective in the first scene to set up the personality and attitude of the main character, Thelonious “Monk” Ellison. A black college professor, he is challenged by a white student on his suggestion to discuss a book with the n-word in the title. In the first few lines, therefore, we find out:

What he teaches and his interests:

“This is a class on the literature of the American south”

And his attitude to the historical use of the n-word in fiction:

“You’re going to encounter some archaic thoughts, and coarse language, but we're all adults here, and I think we can understand it in the context in which it's used.”

Three lines from the character is all it takes to show an accomplished man, with intelligent, mature views. There is a sense of pragmatism and humour in his response to the student that implies that we’re not likely to see immature, overblown behaviour from him. He appreciates that the student is raising the issue based on her own ethics, although he disagrees.

However, then the student continues to push:

MONK With all due respect, Brittany, I got over it. I’m pretty sure you can, too. BRITTANY Well, I don't see why.

And he snaps. The stage directions mention him turning from affable to icy.

The student runs from the room, upset.

We don’t see what he said, but we can fill the blanks.

Our initial idea of the character is now much richer. This is a man with fuse, and one who is capable (and willing) to use his intellect to overcome obstacles, even if it means upsetting people. Was the image he projected just a moment before a facade? Or is this loss of control/temper something that we can expect for the rest of the movie?

The interaction also has the potential to divide the audience. I love it when writing does this, especially so early on. Should Monk, as an educator, have shown more understanding and a nurturing attitude toward the student? Or was he, in the circumstances, justified in his outburst? The moral compass of a reader is immediately engaged.

So in less than one page of dialogue, we have found out:

- A sense of his ethics.

- How he reacts to challenge.

- How do we differ (or agree) with him?

And so, we are all invested in Monk.

Just. Wow.

What can writers learn from this?

Introducing characters is never easy. These are bundles of emotion and ethics and everything else that makes us human, so how do you get that across to readers/viewers in such a short period of time?

This shows that the key is revealing character through a reaction to a dilemma or conflict. It doesn’t have to be a big conflict, but the best ones are those that are easily understood and emotive – both for the reader and the character.

Writers could also try to make the dilemma one the audience will form an opinion of. Doing this forces the reader to get involved with the story, at least subconsciously, because they will be thinking about what they would do in a similar situation. Whether they agree with the character or not, they will want to keep reading or watching to see if the character gets their reward/comeuppance.

American Fiction: Introducing Theme

What the scene also does well is introduce key themes that will sit across the movie.

I often struggle both understanding and conveying the theme at the beginning of my work. I think it’s because of the way that I come up with ideas. Usually, it’s a ‘that would be cool’ moment rather than ‘I want to say this’. This means that I’ve often had feedback that highlights the lack of clarity around my theme and why this story exists (turns out that ‘it might be cool’ isn’t a good enough reason).

Throughout the first part of the movie, Monk battles against what and how he is expected to act and what he is expected to write because of his race.

He meets and is tested by characters with different opinions on this. Each is reacting to the world that surrounds Monk – by either embracing stereotypes or rebelling against them in various ways. Monk is challenged to look at his own moral code and see if his position is the right one.

The balance between expectations of race and personal views are tested throughout.

This theme is set out with a really clear micro-example in the first few moments. What American Fiction does expertly is set that up quickly. As the white student tells the black professor how he should feel about the n-word a specific argument erupts that acts as a proxy for everything that will happen in the next 100 pages, and does it in a way that is clear and easy for the audience to understand.

What writers should think about

Just like writing a synopsis, or pulling together a log line for a script, going small is often more difficult than going big. I write things for work that often have to explain complex and complicated positions succinctly, and it’s really difficult not to put more detail and more explanation down to add weight to your point.

Creative writing is no different. There’s a temptation to throw loads of detail and information in at the beginning. Writers know the story, they know what they want to say, and they need to make sure that the audience knows it. So it all goes in the first few pages and ends up drowning the reader.

When you have that script ready, being clinical can often seem incredibly difficult. This is, however, exactly what Jefferson did with the first minute of American Fiction. By wrapping his clever subtext in a conflict he was able to explain the theme and do it with a single page.

Again - wow.

Key learning

So, what are the key takeaways from one page of this script? Can I break it down into something short and quick? Difficult, but I think it’s something like:

- Be clear about the main character’s traits and test them as quickly as possible.

- Try and make the first scene a microcosm of my entire story’s theme.

Easier said than done.

That’s a lot of learning to be taken from one page.

Wow.

Post-script

I’ve enjoyed writing this. I think it fits more in with the theme (!) of my blog (i.e. what I’ve learnt along the way as I get my book deal) more than my usual ramblings. Therefore, you may see a lot more posts along these lines in the coming weeks and months, as I pull apart a bit of writing that I think is excellent and show what I’ve learnt.

Hopefully, the writers amongst you will also feel the same.

Until then, happy writing.

Phil